London may not be the world’s most beautiful city but it is probably its most storied. Almost every street corner has a story to tell: about rock music, Charles Dickens, Jack the Ripper and so on – the list of themes is virtually endless.

London is also the capital of spy stories, and the most thrilling of these is the one about the Cambridge Five. Or four, or six, or twenty: nobody appears to agree exactly how many graduates of Britain’s second elite university were betraying state secrets to Russia in the 1940s and 1950s.

What’s more, there is hardly a leading figure in the contemporary world of shadows – directors of spy agencies, government ministers, senior military officers – who has not been suspected at one time or the other (or still is) to be the 6th man. Or the 7th, or the nth: just write in your own number.

Why is this such a great story? Because – like the best works of Shakespeare and Alfred Hitchcock – it contains everything: suspense, the drama of real blood and heartbreak, but also much which is darkly funny.

We laugh, mainly, out of sheer disbelief: seen from today, it is barely believable how such unbalanced men who were so obviously ill-suited for a career in the intelligence services, could ever be trusted to act as the guardians of state secrets.

Virtually all of the Cambridge Five had “security risk” written all over them in not-all-that-invisible ink: most of them were gay or bisexual, heavy drinkers who loved to brag about their double lives when inebriated and who dropped stolen top secret documents on pub floors.

The Americans were livid when they found out such details of people they had been told they could trust, and even the Russians – as recently published documents have revealed – dismissed them as men of little substance or worth.

So how could they rise so high in the world of military intelligence? Well, the answer is: because they all went to the right schools. We laugh, but back then, that was all that was ever asked.

Theirs was a small world of leafy streets, gentleman’s clubs and fine dining establishments: small enough to visit some of the key locations from their story in a short, 2-hour walk.

The Cambridge Five in London

We start at Oxford Circus and turn right from Oxford Street into the district of Marylebone, continuing westward in the direction of Cavendish Square. This is an oddly fitting setting for our story, since it is not the posh-est of London neighbourhoods but posh enough to “pass”.

Marylebone is the area where Donald Maclean grew up, one of the key characters in our story and the only one who was a member of Britain’s “ruling class” in the narrow sense of the word, a career diplomat from a family of high-minded patricians whose father had served as a cabinet minister.

It is also the area where Anthony Blunt and Guy Burgess, two more members of the Cambridge Five in London, once inhabited a building on 5 Bentinck Street, …

… a famous centre of London’s bohemian life in the 1940s which, at the time, belonged to the Rothschild family.

It was probably not their only property in town, but one that was sufficiently far down the list to accommodate second-tier house guests such as down-at-heel gentlemen with the right (i.e. “progressive”) world views.

A little further to the west, you will find Portman Square where, at no. 20, the Courtauld Institute of Art resided in the 1950s, when Anthony Blunt was its director.

Blunt, one of the Cambridge Five in London, was art advisor to the Queen (on top of being a blood relative, through her mother) and the world’s leading authority on Poussin. He was also a Soviet spy, in fact the recruitment officer of the KGB’s Cambridge cell in the 1930s.

He confessed (in exchange for full immunity from prosecution) to what he doubtlessly saw as his “youthful indiscretions” in 1962 when he had firmly landed with both feet on the side of the British establishment. It did not go unnoticed at the time, nevertheless, that he only seemed to tell his interrogators what they already knew and that he only incriminated people who were safely out of reach.

We return to Oxford Street now and cross over into Mayfair. Mayfair is posher than Marylebone, but also more rakish: this was originally the district where gentlemen used to house their mistresses, and today, it is from here that the raffish end of the financial trade operates (hedge funds).

Mayfair was the world of Guy Burgess, the most “mad, bad and dangerous to know” of the Cambridge Five (and the only one who would eventually be portrayed by Rupert Everett on both the London stage and the cinematic screen.

Retracing his last day in London, we start at Clifford Chambers on 10 Bond Street, where Guy Burgess would have woken up in his flat on the morning of 25 May 1951.

Burgess had only recently returned from the UK’s Washington Embassy, having been more or less fired from his job (after a series of episodes of “unseemly behaviour” had culminated in him being caught speeding three times on a single day).

Mid-morning Burgess received a telegram from the cell’s ringleader Kim Philby, a career intelligence officer at the Washington Embassy (more of him later), with clear codified instructions.

Maclean had come under increasing suspicion of being a Soviet mole, and Philby had learned that an interrogation was being planned for the following Monday. Concerned that Maclean would crack, his Russian handlers had decided it was time for him to defect to Moscow – and for Burgess to help him on his way.

Ostensibly referring to the car Burgess had abandoned in the Embassy car park, Philby wired him: “If you do not act at once it will be too late,” the telegram read, “because they will send your car to the scrap heap.”

Burgess had to inform Maclean as soon as possible, but did not want to contact him immediately because his friend was still – under close observation – at his desk in the Foreign Office. So a nervous Burgess had to kill time and went to the Half Moon Hotel on Half Moon Street (now the Hilton Green Park)…

… to meet an American student he had met on the boat back from the US.

Together, they went for a walk in near-by Green Park, …

… and Burgess confessed to his acquaintance – as the young American later reported – that he was “extremely upset” because one of his friends at the Foreign Office was in serious trouble.

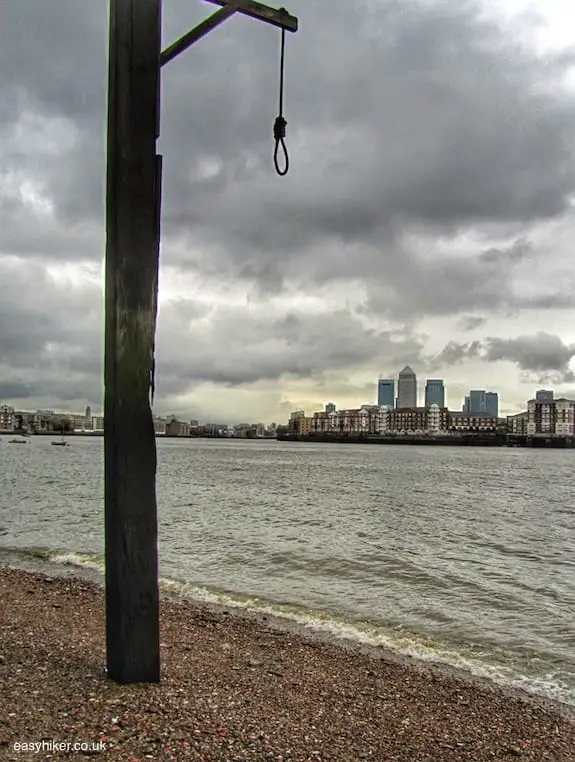

From there, Burgess walked to Pall Mall, the area of London where you could (and can) find all the most prestigious gentleman’s clubs. He had lunched with MacLean at the Royal Automobile Club a few days before, undoubtedly discussing the tightening noose around their necks.

On this day, he went a few houses further up the street to his own club, the Reform on no. 104, to use their phone for hiring a car. Burgess then picked up the car (at Crawford Street, a mile or so to the north) and drove straight to his tailor at 27 Old Bond Street (Gieve’s, now famously located at 1 Saville Row), to purchase a suitcase and a warm overcoat. After all, what else is a gentleman to do before a possibly rather long journey abroad?

He then called Maclean at his house in suburban Kent, ostensibly to congratulate him on his birthday (which it was) and telling him he’d drop by in the evening. Burgess’s boyfriend, with whom he shared the flat, later remembered his flat-mate as “visibly distressed” after the conversation.

Burgess quickly said good-bye to his boyfriend and drove to Kent for a quiet family dinner with the Macleans, at the end of which Mrs. Maclean was informed that her husband and his visitor would go away for a brief business trip.

Maclean and Burgess just about made it to Southampton for the day’s last ferry to France, having to leave their car on the quayside as they hurried up the gangway. “Never mind the car”, Burgess shouted to the ferry handlers, “We will be back on Monday”. In fact, neither he nor Maclean were ever to return to Britain.

To be continued! Do not miss the conclusion of this story in next week’s post – when we will also have some fun, visiting some of the Cold War’s most famous “dead letter drops”!