For this post, our last before the holidays, I wanted to fulfill as many Christmas wishes as I possibly could.

Which meant that, since I had no idea what anyone of you might want me to write about, there was only a single Christmas wish that I positively knew I could fulfill, which was my own. (Sorry if that sounds selfish, but the logic is irrefutable.)

I would, however, feel privileged if you were to accompany me on my visit to one of London’s most iconic places.

For me, this was a wish I had harboured for many years (I had already lost hope that it could ever come true), and I hope that I can instill in you a wish to visit this long-forgotten corner of London, too.

You don’t even have to wait for (next year’s) Christmas, because the place we are going to see has woken up from a Rip-van-Winkle-like deep sleep and is, for the first time ever, open for the public throughout the year.

For several years, I used to pass Battersea Power Station every day on my way to work in central London. Even before I knew the building’s fascinating back story, I was intrigued by its tragic aura.

In what was then a low-rise neighbourhood of warehouses and wholesalers’ markets, the disused power station looked not only out of place – like a beached whale – but also out of time: an archaic temple for the God Of Heavy Industry amid the unheroic, dwarfish shacks of low commerce.

How in the world did it get there?

Battersea Power Station was built in two phases from 1930 until the late 1940s. The government policy at the time was to replace the then-existing network of small electricity generators with large power stations that were meant to operate in close vicinity to residential and commercial areas.

In the end, only two such stations were built: Battersea and Bankside (now the Tate Modern), both designed by the architect Giles Gilbert Scott who had also created the iconic red telephone box.

The UK government’s power policy changed after WWII and, perhaps more relevantly, after the deadly smog of 1951, when the idea of encircling London’s town centre with a ring of enormous coal-fired power stations no longer seemed so cunning.

When Battersea Power Station was shut down in 1975, the owners’ first wish was to have it torn down, since this was by far the cheapest option, but the government pre-empted any such plan by putting the entire structure on the list of national heritage sites.

How do you repurpose a disused industrial building which is larger than St Paul’s Cathedral?

Over the years, dozens of schemes were developed, ranging from the whimsical (a theme park) and the fanciful (a new stadium for Chelsea FC) to the downright fantastic (an “Eco dome”).

Eventually, however, they all fell through, and even the involvement of star-studded architects such as Rafael Vinoly and Nicholas Grimshaw came to nothing.

For Battersea Power Station, these were decades of decay, and the structure deteriorated to the point where it was (in 2008) put on the National Heritage At Risk register. But at the same time, in a strange twist of the story, this decay only served to enhance the building’s iconic status: throughout this period, Battersea became the number one address for every British film and cop show producer who was looking for a scenic industrial wasteland.

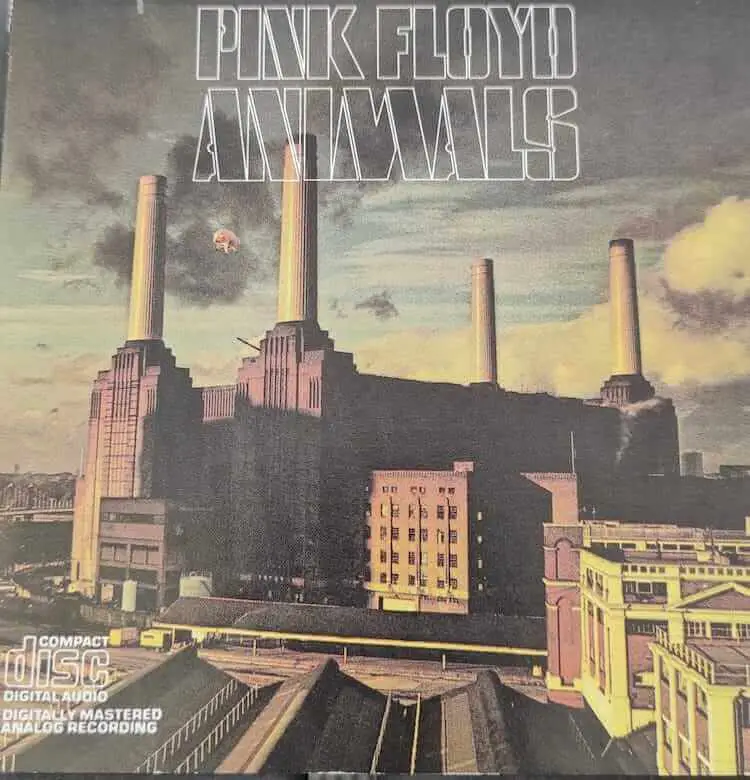

On top of that, movie stardom was accompanied by a support part in rock music history when the station featured on the cover of a celebrated 1970s album.

Eventually, a commercially viable solution was found for Battersea Power Station when a consortium of investors from Malaysia decided to pump nearly 10 billion pounds into the development of a mixed commercial and residential project.

Frank Gehry was hired to design a couple of signature apartment blocks …

… which, together with a pedestrianized shopping zone, now stand where once coal would have been unloaded or stored.

No attempt, meanwhile, has been made to outshine the station itself, which stands, in more than one way, at the centre of it all.

In fairness: outshining the station would have been a difficult task, not least because it is so massive (the largest brick structure in Europe) and so gigantic (160 x 170 meters) …

… but also because it is such an architectural heavyweight. It is not only through its bulk that the station puts the other buildings in its shadow: it is also through its uncompromising starkness, its seriousness of purpose.

The interiors of the power station have undergone a thorough redesign to prepare the building for its new role as a shopping centre.

Much of this is new, but there are also many nods to the building’s history.

Control Room B, still fitted out with some of the historical equipment, is now a restaurant …

… while Control Room A has been fully restored to its 1930s self and turned into an event space with limited general access.

If you want to see it, however, you can watch it on film: the room was used for the scene in “The King’s Speech” where the (then) Duke of York delivers a radio speech from Wembley Stadium. If you are interested in historic power station technology, there are other pieces of the old equipment on show in many corners of the new shopping centre.

After exploring the building, you can take a walk around in its surroundings. Bear in mind that an entire new town is being created here, one where 25,000 people will eventually be living and working in one of London’s largest office, retail and leisure quarters.

If you believe that your feet will still be itching after such a stroll, we suggest you combine your trip to Battersea Power Station with a visit of Battersea Park which is only a 10-minute-walk away.

We also suggest you go to the park first, ideally in the morning, which means that you will arrive on time for a (late) lunch in the station’s semi-finished Food Court.

On the way, there are other things to see as well, and you should not miss Battersea’s second most famous building: the Dogs Home which was one of the first such institutions in the world when it was founded in 1860.

Peek through the iron doors for a glimpse of Whittington Lodge, Britain’s first stray cat asylum, …

… built in the early 20th century by the eccentric architect Clough Williams-Ellis who is best known for the construction of the village of Portmeirion in Wales, half Italian village and half proto-surrealist fantasy. You may have seen Portmeirion on TV: the 1960s television series “The Prisoner” was filmed there (“I am not a number, I am a free man!”).

Return to Central London from the new Battersea Park station on the ultra-modern Northern Line extension that was built as part of the development. This is an experience in itself – and a perfect way to round off a day-out in London like no other!