Water. If you want to know what shapes and sustains the Mediterranean way of life, just follow its flow.

Drinking water is the magical essence of the Mediterranean alchemy. It turns scruffy woodlands into orchards and lush gardens, baking-hot courtyards into oases of coolness and calm, and parched savannahs into fertile fields that can sustain urban settlements with hundreds of thousands of inhabitants.

Without water, there would be life around the Mediterranean but not life as we know it. Nearly everything would look like the barren mountains of central Greece and the deserts of Extremadura in western Spain. Add water, however, and you get Athens, Rome and Carthage – civilization, in one word.

And within these Mediterranean civilizations, water has another important function: its waste has always served as a means of displaying wealth and power.

In the evolution of nations and their power structures, water has played a similar role to the roles of antlers and colourful feather coats in the evolution of certain biological species: alpha individuals and alpha groups display their often frivolous use of water, exactly because it is such a scarce and precious resource.

The ancient Romans were the masters of such displays of power. But wherever they went, they left behind not only monumental aqueducts and public baths, but also the ingrained attitudes that created the desire for them.

To this very day, it appears that the civic pride of Mediterranean cities dictates the prodigal use of water.

Follow the Water for a Lesson in Sicilian History

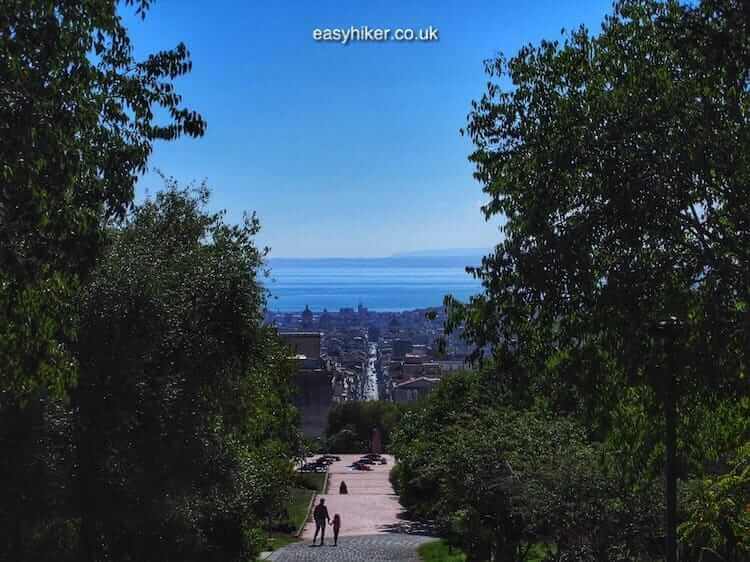

Without generous supplies of water, for example, Catania’s Giardini Bellini would hardly look the way they do – in a city that has always hovered around the threshold of semi-aridity.

The story of Catania’s water is inextricably linked with the city’s tumultuous history. The early inhabitants of Catania got most of their water from the network of streams and lakes around the Amenano river

Already in antiquity, this river was under constant threat of drying up or of being permanently diverted by eruptions of Mount Etna. (In the Metamorphoses, the Roman poet Ovid says that the Amenano was “dragging Sicilian sands” to the coast).

It was clearly the best solution to connect the city to the fresh water sources of Leucatia a few kilometres to the north. Which is exactly what the ancient Romans did.

No contemporary sources mention the construction of such an aqueduct, but we have the evidence of the hardware: parts of the ancient structure survive, and so does a plaque on a pillar that has been reliably identified as a relict from the period of the Emperor Augustus.

The first documents that mention the aqueduct have come down to us from the 15th century. These sources describe the structures as “monumental” and compare their scale to the water supplies of Rome herself.

Virtually nothing of this structure, however, is left in downtown Catania. To discover the ruins of the ancient aqueduct, you must climb up the Canilicchio hill that leads to the Park Gioeni in the city’s northern outskirts, a brief walk up Via Etnea from the metro station Borgo.

Some of the aqueduct’s remnants in this busy but slightly scruffy city park are well preserved …

… while others have been re-purposed over time, are overgrown or both.

At some stage in the 16th century, this ancient water supply system must have fallen into disrepair and neglect. We know this because in 1556, an edict issued by the Spanish Viceroy ordered the destruction of what had been left over from the downtown aqueduct – apparently no longer in use at the time – to provide his troops with building materials for city wall reinforcements.

Once again, Catania came to rely on the Amenano river and near-by Lake Nicito for its drinking water, unreliable and low-quality resources as they may have been.

This went on for about 100 years until, in the 1640s, Benedictine monks had the idea of combining two building projects on land that they had recently purchased: one, a retirement home for elderly members of their order on the top of Leucadia Hill, and second – to help finance the first – an aqueduct to carry the abundant fresh water from the springs on this territory into the heart of the city.

Fundamentally, this project was a commercial enterprise and therefore ruled by commercial logic. As a consequence, the Benedictines used as much of the remaining Roman aqueduct as they could – and we must thank them for their thrift, because the ancient ruins would surely be gone today if they had not been integrated into an updated supply system.

As it is, however, we can still follow the route the Roman water must have taken for 1500 years, simply by following Via Angelo Musco (which becomes Via Leucatica after a few blocks) northwards from the Parc Gioeni.

This will lead you straight (after approx. 1 km) to the Timpa della Leucatia where you can spot some particularly well-preserved parts of the ancient structure.

But what is really striking about the land underneath the Benedictine retirement home from the 17th century is its lushness.

This is not the lushness of Bellini Gardens, but its rougher and more street-wise cousin. The Leucatia springs still produce about 5 billion litres of water every year, and, what is more, water of an excellent quality, coming from an aquifer that is supplied by the melting snows of Mount Etna.

And if you manage to make your way inside, it will not be long before you can find, even today in this feral landscape, what the ancient Romans and then the Benedictine monks came here for all these years ago.

Do not expect the walk from Borgo station to the Timpa della Leucatia to deliver much in terms of delicacy or elegance. But while the walk may be short on beauty, it is long on insight – insights such as this: the sources of Sicily’s ancient wealth are still all there, but they appear to have been poorly managed for centuries.

Traces of the island’s ancient glory are barely acknowledged by an impoverished present and exist on the periphery of everyday life, in this case inside a scruffy suburban park and a totally abandoned piece of feral countryside. Plans to create a “tourist route” along the path of the ancient waterway exist but have so far led to nothing.

And from what I think I know about Italy, I would advise you not to hold your breath. But at least, until such a trail has been officially inaugurated, you can now follow your very own Easy Hiker route.

Finally, a few words about one hike that we did not do. Many visitors of eastern Sicily make the trip up Mount Etna, undoubtedly the area’s most prominent and most famous feature, but we, eventually, decided not to. And here is why.

We decided to waive this trip after hearing what our landlord – the ever helpful Santo who knew about our interest in hiking – had to say on the subject. This is what he told us.

There is only one bus a day from Catania to Mount Etna. It leaves from outside the central station at 8 in the morning and takes you to the main refuge on the volcano’s southern slope. It then returns in mid-afternoon – approx. six hours later – to pick you up again.

Six hours: is that a lot? This depends on how you are planning to fill your time. If you want to go (nearly) all the way up the peak of the volcano, you will certainly have no time to waste.

This, however, is quite an operation, and it won’t come you cheap: first, there is the cable car (€ 30 p.p.) from the refuge, following which you must continue your journey in a small 4×4 bus (€24 p.p.) and then on foot from its drop-off point to the lowest craters near the summit.

For this last part of your journey, you are strongly encouraged to use one of the guides who are waiting at the bus terminal (€10 p.p.) since there are no marked or defined “paths” beyond the cable car station.

Alternatively, you can … well, walk around the refuge a little. Going by what can be seen on Google street view, however, this is a uniquely bleak landscape, the perfect stage set for a Samuel Beckett play, not for a pleasant holiday experience. (Two easy hikers. A road. No tree.)

And if it is cloudy up there (which it often is, 2000 metres up in the sky), you will see even less, perhaps not even as far as the next turn on the road. Which means that you will spend most of the time in the refuge, waiting for the bus. Under these circumstances, six hours can be a very, very long time.

If you are still determined to go for it, make your way to Catania train station. The buses leave at 8 a.m. from the station forecourt inside the roundabout.

Tickets can be purchased only on the day of your departure and only in the coffee shop at the corner of Via Don Luigi Sturzo, on the far side (seen from the station) of the roundabout.

Yes, this is a weird system, but when in Sicily, you should do like the Sicilians. Learn the lesson in Sicilian history. Never ask why, simply accept any hardship as part of the hardship of life.