One thing that makes Tel Aviv particularly interesting is that it is not like any other city on the Mediterranean coast: it bears no visible traces of Roman or Greek heritage – nor, indeed, of any other kind of heritage from before 1909, the year when the city was born.

Still, a great many things have happened since 1909, and all of them have left their mark on Tel Aviv’s urban fabric. It is these marks that we shall discover today.

Last week, we visited the older settlements on the coast that were eventually swallowed up by the growing Tel Aviv.

Today, we are crossing the HaKovshim Gardens – the busy Carmelite traffic junction – into the city itself as we walk from Neve Tzedek into the area around Allenby Street and the Nachalat Binyamin neighbourhood.

This is where the first European Jews settled in the 1920s. They brought the traditions of their old home countries to the new world of Zionist Palestine, but also an understanding that this was not Vienna, and the houses they built reflect this.

Some of these buildings appear a little uncertain of where they are and where to go stylistically, …

… but others are already more assured: the people who settled here undoubtedly saw themselves as Europeans, but they were also willing to make adjustments.

The details of the buildings, meanwhile, can be telling. When not forced to make architectural statements, the people who settled here show that their minds were still inspired by what they had left behind.

The adjacent Kerem HaTimanim quarter is the home for a group of immigrants who found it equally hard to leave their memories behind: the area between HaYarkon and HaCarmel Street was settled by the Yemenite community in the early decades of the 20th century.

Bordering these two quarters, you can find a nice piece of “cultural fusion”: on the one hand, the HaCarmel Market is clearly a souk, that most Oriental of institutions, but it has also been infused by a European sense of space and order.

It may be exotic enough to impress visitors from Northern Europe and the US, but you will only think that this is a ”typical” Oriental market if you have never been to one.

Leave the HaCarmel market via Balfour Street towards the heart of Tel Aviv’s White City, whose architectural heritage has been recognized by the UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

On the first corner to the right, glimpse into Straus Street to get a glimpse of what is expecting you there.

Bruno House was built in 1935 by the architect Ze’ev Rechter (like so many of his peers, a refugee from the persecution of Jews in Europe) – not as an eccentric millionaire’s residence, as one might possibly assume, but as a communal dormitory for teachers from a near-by school.

When the building was renovated in 2004, two new floors were added to the back which can only be glimpsed from street level. This is something relatively common in Tel Aviv: the city appears to protect and maintain its modernist heritage with true passion and dedication, but at the same time refuses to cast it in the amber of strict preservation orders.

Modernism, it seems, is not so much understood as a merely historic movement but rather as a principle of creative activity: as a demand to stay relevant at all times, to look forward rather than back.

At the end of Balfour Street, turn left into Siderot Rothschild, the grandest and most fashionable boulevard of Tel Aviv.

Modernist ideas had been circulating in European architecture at least since the end of WWI – the Bauhaus school was established in 1919 – but had to be introduced carefully and piecemeal into the existing urban environments.

Here, in the New World of Jewish Palestine, no such restrictions existed, and the modernist architects were given a virtual carte blanche by their, quite frequently, wealthy clients.

As a result, Rothschild Boulevard has become an outdoor museum of modern architecture. And like in any first-class museum, there are the world-famous masterpieces, represented here by buildings such as the uncompromisingly austere Krieger House (no. 71) …

… and the elegant Braun-Rabinsky House (no. 82) …

… but, again: in an analogy to fine arts museums, it is as much fun to stroll through the equivalents of less crowded, underappreciated galleries, looking for something interestingly non-perfect rather than something universally celebrated.

There is plenty of that here, too.

Rothschild Boulevard is divided in the middle by a tree-lined pedestrian walkway, one of Tel Aviv’s few green spaces. This provides you with a rare opportunity of catching your breath surrounded by something other than asphalt and concrete.

When you arrive at Habima Square at the top of Rothschild Boulevard, turn left and then, after one block, right into King George before taking another left into Dizengoff Street.

Continue past the Dizengoff Centre – Tel Aviv’s busiest shopping mall – into Dizengoff Square, the heart of the modern city.

This quarter may be overall more lively than beautiful, but Dizengoff Square itself features one of Tel Aviv’s most elegant 1930 buildings, the Hotel Cinema.

Dizengoff Square may also be the right place to sit down for a cup of coffee and to reflect over what you have seen today. You have discovered a city that is different not only from its Mediterranean peers but also from its domestic neighbours.

Jaffa, Haifa, Jerusalem: these were already large settlements when modern Israel took shape. Tel Aviv, conversely, was created ex nihilo: it was, and is, the Zionist project par excellence.

How did this play out? And what would the original Zionists think about the modern city?

They would, I believe, be impressed by the mutual affection and solidarity that appears to underlie so much of everyday social intercourse – smiles and friendly words at supermarket checkout counters, small gestures of kindness in traffic and public transport.

If you have started last week’s walk by taking the bus to Jaffa, for example, there is a good chance that you will have witnessed a young person offering his or her seat to an older one. They still do that over there – and it is not just children standing up for old women on crutches, but 30-year-olds for 60-year-olds. You will not see anything like that in Paris or London.

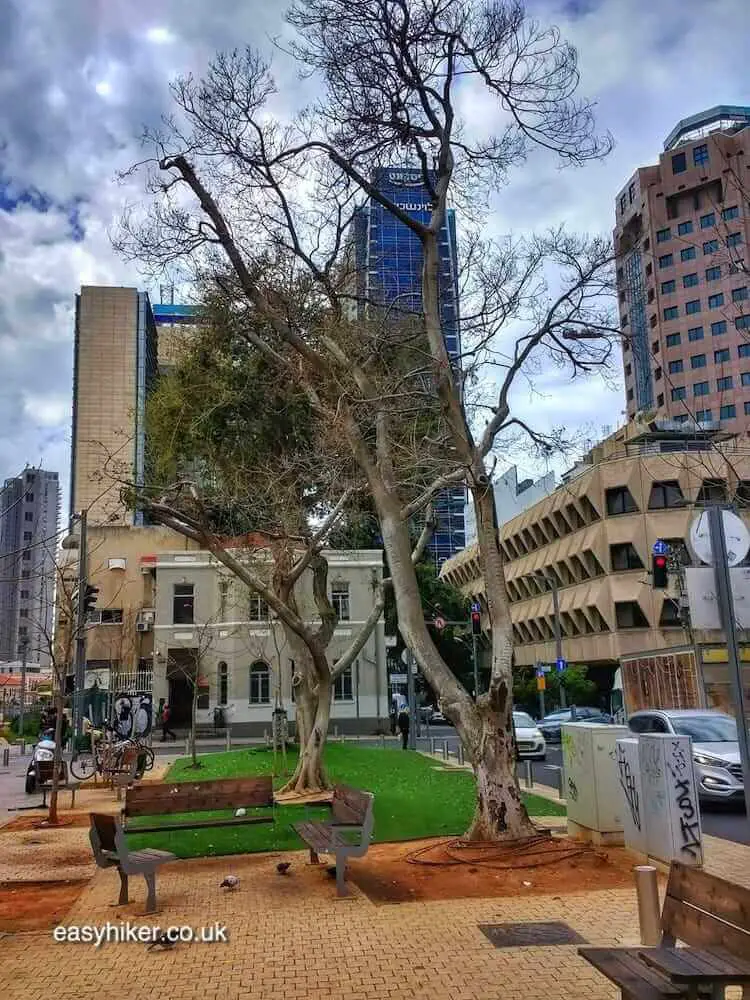

I am less certain how happy these pioneers of Zionist Tel Aviv – socialists virtually to a man and woman – would be with the looks of the modern city. The intrusion of US-style skyscrapers into the city’s skyline …

… may very well, after all, be a mere symbol for Israel’s gradual abandonment of European social traditions and attitudes in favour of a more muscular, American individualism.

Where these European traditions appear to be under siege by their overpowering rival,…

… these pioneers would, I suspect, take the side of the little guy.